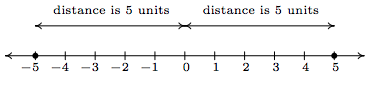

There are a few ways to describe what is meant by the absolute value \(|x|\) of a real number \(x\). You may have been taught that \(|x|\) is the distance from the real number \(x\) to \(0\) on the number line. So, for example, \(|5| = 5\) and \(|-5| = 5\), since each is \(5\) units from \(0\) on the number line. Another way to define absolute value is by the equation \(|x| = \sqrt\). Using this definition, we have \(|5| = \sqrt = \sqrt = 5\) and \(|-5| = \sqrt = \sqrt = 5\). The long and short of both of these procedures is that \(|x|\) takes negative real numbers and assigns them to their positive counterparts while it leaves positive numbers alone. This last description is the one we shall adopt, and is summarized in the following definition.

Definition 2.4: Absolute Value The absolute value of a real number \(x\), denoted \(|x|\), is given by \[ |x| = \left\< \begin -x, & \mbox & x < 0 \\ x, & \mbox& x \geq 0 \\ \end \right. \label\]

In Definition 2.4, we define \(|x|\) using a piecewise-defined function (Section 1.4). To check that this definition agrees with what we previously understood as absolute value, note that since \(5 \geq 0\), to find \(|5|\) we use the rule \(|x| = x\), so \(|5|=5\). Similarly, since \(-5 < 0\), we use the rule \(|x| = -x\), so that \(|-5| = -(-5) = 5\). This is one of the times when it's best to interpret the expression '\(-x\)' as 'the opposite of \(x\)' as opposed to 'negative \(x\)'. Before we begin studying absolute value functions, we remind ourselves of the properties of absolute value.

Equality Properties:

The proofs of the Product and Quotient Rules in Theorem 2.1 boil down to checking four cases:

For example, suppose we wish to show that \(|ab| = |a||b|\). We need to show that this equation is true for all real numbers \(a\) and \(b\). If \(a\) and \(b\) are both positive, then so is \(ab\). Hence, \(|a| = a\), \(|b| = b\) and \(|ab| = ab\). Hence, the equation \(|ab| = |a||b|\) is the same as \(ab = ab\) which is true. If both \(a\) and \(b\) are negative, then \(ab\) is positive. Hence, \(|a| = -a\), \(|b| = -b\) and \(|ab| = ab\). The equation \(|ab| = |a||b|\) becomes \(ab = (-a)(-b)\), which is true. Suppose \(a\) is positive and \(b\) is negative. Then \(ab\) is negative, and we have \(|ab| = -ab\), \(|a| = a\) and \(|b| = -b\). The equation \(|ab| = |a||b|\) reduces to \(-ab = a(-b)\) which is true. A symmetric argument shows the equation \(|ab| = |a||b|\) holds when \(a\) is negative and \(b\) is positive. Finally, if either \(a\) or \(b\) (or both) are zero, then both sides of \(|ab| = |a||b|\) are zero, so the equation holds in this case, too. All of this rhetoric has shown that the equation \(|ab| = |a||b|\) holds true in all cases.

The proof of the Quotient Rule is very similar, with the exception that \(b \neq 0\). The Power Rule can be shown by repeated application of the Product Rule. The 'Equality Properties' can be proved using Definition 2.4 and by looking at the cases when \(x\geq 0\), in which case \(|x| = x\), or when \(x0\), and \(|x| = c\), then if \(x \geq 0\), we have \(x = |x| = c\). If, on the other hand, \(x < 0\), then \(-x = |x| = c\), so \(x = -c\). The remaining properties are proved similarly and are left for the Exercises. Our first example reviews how to solve basic equations involving absolute value using the properties listed in Theorem 2.1.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Absolute Value

Solve each of the following equations.

Solution

To use the Equality Properties to solve \(3 - |x+5| = 1\), we first isolate the absolute value.

From the Equality Properties, we have \(x+5 = 2\) or \(x+5 = -2\), and get our solutions to be \(x = -3\) or \(x = -7\). We leave it to the reader to check both answers in the original equation.

Next, we turn our attention to graphing absolute value functions. Our strategy in the next example is to make liberal use of Definition 2.4 along with what we know about graphing linear functions (from Section 2.1 ) and piecewise-defined functions (from Section 1.4).

Graph each of the following functions.

Find the zeros of each function and the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts of each graph, if any exist. From the graph, determine the domain and range of each function, list the intervals on which the function is increasing, decreasing or constant, and find the relative and absolute extrema, if they exist.

Solution

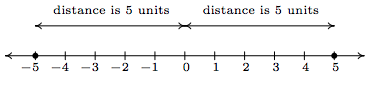

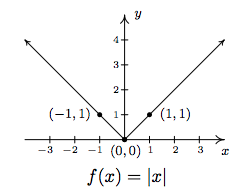

By projecting the graph to the \(x\)-axis, we see that the domain is \((-\infty, \infty)\). Projecting to the \(y\)-axis gives us the range \([0,\infty)\). The function is increasing on \([0,\infty)\) and decreasing on \((-\infty,0]\). The relative minimum value of \(f\) is the same as the absolute minimum, namely \(0\) which occurs at \((0,0)\). There is no relative maximum value of \(f\). There is also no absolute maximum value of \(f\), since the \(y\) values on the graph extend infinitely upwards.

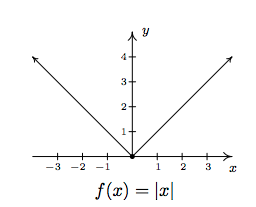

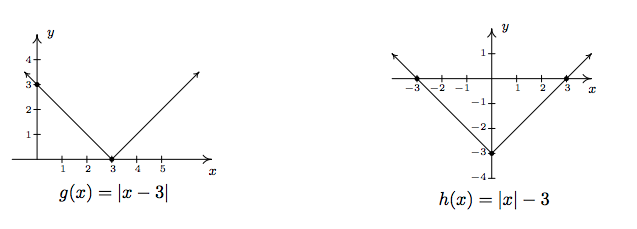

2. To find the zeros of \(g\), we set \(g(x) = |x-3|=0\). By Theorem 2.1, we get \(x-3=0\) so that \(x=3\). Hence, the \(x\)-intercept is \((3,0)\). To find our \(y\)-intercept, we set \(x=0\) so that \(y = g(0) = |0-3| = 3\), which yields \((0,3)\) as our \(y\)-intercept. To graph \(g(x) = |x-3|\), we use Definition 2.4 to rewrite \(g\) as

Simplifying, we get

As before, the open circle we introduce at \((3,0)\) from the graph of \(y = -x+3\) is filled by the point \((3,0)\) from the line \(y = x-3\). We determine the domain as \((-\infty, \infty)\) and the range as \([0,\infty)\). The function \(g\) is increasing on \([3,\infty)\) and decreasing on \((-\infty,3]\). The relative and absolute minimum value of \(g\) is \(0\) which occurs at \((3,0)\). As before, there is no relative or absolute maximum value of \(g\).

3. Setting \(h(x) = 0\) to look for zeros gives \(|x|-3=0\). As in Example \(\PageIndex\), we isolate the absolutre value to get \(|x| = 3\) so that \(x =3\) or \(x=-3\). As a result, we have a pair of \(x\)-intercepts: \((-3,0)\) and \((3,0)\). Setting \(x=0\) gives \(y = h(0) = |0|-3 = -3\), so our \(y\)-intercept is \((0,-3)\). As before, we rewrite the absolute value in \(h\) to get

Once again, the open circle at \((0,-3)\) from one piece of the graph of \(h\) is filled by the point \((0,-3)\) from the other piece of \(h\). From the graph, we determine the domain of \(h\) is \((-\infty, \infty)\) and the range is \([-3,\infty)\). On \([0,\infty)\), \(h\) is increasing; on \((-\infty,0]\) it is decreasing. The relative minimum occurs at the point \((0,-3)\) on the graph, and we see \(-3\) is both the relative and absolute minimum value of \(h\). Also, \(h\) has no relative or absolute maximum value.

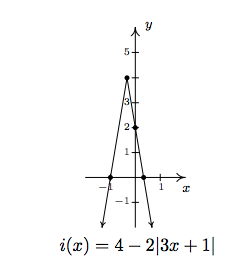

4. As before, we set \(i(x)=0\) to find the zeros of \(i\) and get \(4 - 2|3x+1|=0\). Isolating the absolute value term gives \(|3x+1|=2\), so either \(3x+1 = 2\) or \(3x+1=-2\). We get \(x=\frac\) or \(x=-1\), so our \(x\)-intercepts are \(\left(\frac,0\right)\) and \((-1,0)\). Substituting \(x=0\) gives \(y = i(0) = 4-2|3(0)+1| = 2\), for a \(y\)-intercept of \((0,2)\). Rewriting the formula for \(i(x)\) without absolute values gives

The usual analysis near the trouble spot \(x=-\frac\) gives the 'corner' of this graph is \(\left( -\frac, 4\right)\), and we get the distinctive '\(\vee\)' shape:

The domain of \(i\) is \((-\infty, \infty)\) while the range is \((-\infty, 4]\). The function \(i\) is increasing on \(\left(-\infty, -\frac\right]\) and decreasing on \(\left[ -\frac, \infty\right)\). The relative maximum occurs at the point \(\left(-\frac, 4\right)\) and the relative and absolute maximum value of \(i\) is \(4\). Since the graph of \(i\) extends downwards forever more, there is no absolute minimum value. As we can see from the graph, there is no relative minimum, either.

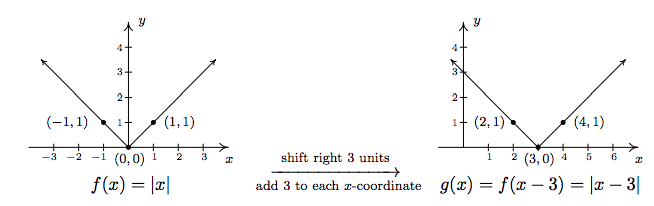

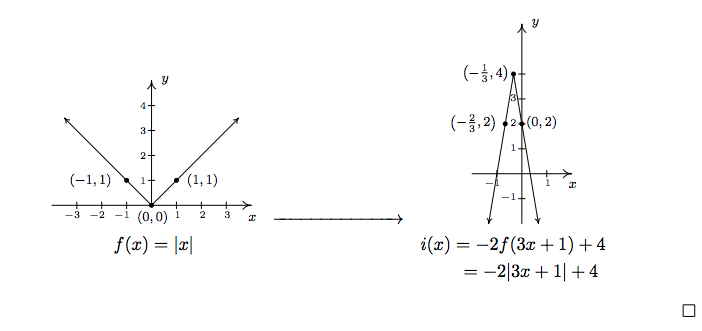

Note that all of the functions in the previous example bear the characteristic '\(\vee\)' shape of the graph of \(y=|x|\). We could have graphed the functions \(g\), \(h\) and \(i\) in Example \(\PageIndex\) starting with the graph of \(f(x)=|x|\) and applying transformations as in Section 1.7 as our next example illustrates.

Graph the following functions starting with the graph of \(f(x) = |x|\) and using transformations.

Solution

We begin by graphing \(f(x) = |x|\) and labeling three points, \((-1,1)\), \((0,0)\) and \((1,1)\).

2. For \(h(x) = |x| - 3 = f(x) -3\), Theorem 1.7 tells us to subtract \(3\) from each of the \(y\)-values of the points on the graph of \(y=f(x)\) to obtain the graph of \(y = h(x)\). This shifts the graph of \(y=f(x)\) down \(3\) units and moves \((-1,1)\) to \((-1,-2)\), \((0,0)\) to \((0,-3)\) and \((1,1)\) to \((1,-2)\). Connecting these points with the '\(\vee\)' shape produces our graph of \(y=h(x)\).

3. We re-write \(i(x) = 4-2|3x+1| = 4-2f(3x+1) = -2f(3x+1) + 4\) and apply Theorem 1.7. First, we take care of the changes on the 'inside' of the absolute value. Instead of \(|x|\), we have \(|3x+1|\), so, in accordance with Theorem 1.7, we first subtract \(1\) from each of the \(x\)-values of points on the graph of \(y = f(x)\), then divide each of those new values by \(3\). This effects a horizontal shift left \(1\) unit followed by a horizontal shrink by a factor of \(3\). These transformations move \((-1,1)\) to \(\left(-\frac, 1 \right)\), \((0,0)\) to \(\left(-\frac, 0 \right)\) and \((1,1)\) to \(\left(0,1\right)\). Next, we take care of what's happening 'outside of' the absolute value. Theorem 1.7 instructs us to first multiply each \(y\)-value of these new points by \(-2\) then add \(4\). Geometrically, this corresponds to a vertical stretch by a factor of \(2\), a reflection across the \(x\)-axis and finally, a vertical shift up \(4\) units. These transformations move \(\left(-\frac, 1 \right)\) to \(\left(-\frac, 2 \right)\), \(\left(-\frac, 0 \right)\) to \(\left(-\frac, 4 \right)\), and \(\left(0,1\right)\) to \(\left(0, 2\right)\). Connecting these points with the usual '\(\vee\)' shape produces our graph of \(y = i(x)\).

While the methods in Section 1.7 can be used to graph an entire family of absolute value functions, not all functions involving absolute values posses the characteristic '\(\vee\)' shape. As the next example illustrates, often there is no substitute for appealing directly to the definition.

Graph each of the following functions. Find the zeros of each function and the \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercepts of each graph, if any exist. From the graph, determine the domain and range of each function, list the intervals on which the function is increasing, decreasing or constant, and find the relative and absolute extrema, if they exist.

Solution

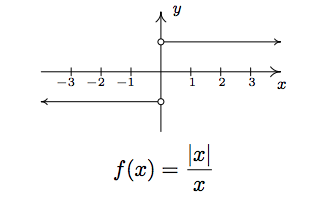

To graph this function, we graph two horizontal lines: \(y = -1\) for \(x < 0\) and \(y = 1\) for \(x >0\). We have open circles at \((0,-1)\) and \((0,1)\) (Can you explain why?) so we get

As we found earlier, the domain is \((-\infty, 0)\cup(0,\infty)\). The range consists of just two \(y\)-values: \(\\). The function \(f\) is constant on \((-\infty,0)\) and \((0,\infty)\). The local minimum value of \(f\) is the absolute minimum value of \(f\), namely \(-1\); the local maximum and absolute maximum values for \(f\) also coincide \(-\) they both are \(1\). Every point on the graph of \(f\) is simultaneously a relative maximum and a relative minimum. (Can you remember why in light of Definition 1.11? This was explored in the Exercises in Section 1.6 .)

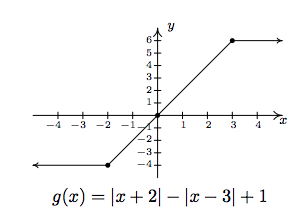

2. To find the zeros of \(g\), we set \(g(x) = 0\). The result is \(|x+2|-|x-3| +1 = 0\). Attempting to isolate the absolute value term is complicated by the fact that there are \textbf terms with absolute values. In this case, it easier to proceed using cases by re-writing the function \(g\) with two separate applications of Definition 2.4 to remove each instance of the absolute values, one at a time. In the first round we get

The domain of \(g\) is all real numbers, \((-\infty, \infty)\), and the range of \(g\) is all real numbers between \(-4\) and \(6\) inclusive, \([-4,6]\). The function is increasing on \([-2,3]\) and constant on \((-\infty, -2]\) and \([3,\infty)\). The relative minimum value of \(f\) is \(-4\) which matches the absolute minimum. The relative and absolute maximum values also coincide at \(6\). Every point on the graph of \(y=g(x)\) for \(x 3\) yields both a relative minimum and relative maximum. The point \((-2,-4)\), however, gives only a relative minimum and the point \((3,6)\) yields only a relative maximum. (Recall the Exercises in Section 1.6 which dealt with constant functions.)

Many of the applications that the authors are aware of involving absolute values also involve absolute value inequalities. For that reason, we save our discussion of applications for Section 2.4.

3.5: Absolute Value Functions is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.